1n 1995, Doordarshan, the Indian National Broadcaster, aired a series of thirteen episodes in Hindi called ‘Amaravati Ki Kathayen‘, which was an anthology of short stories and snippets from the daily life of the people of a town called Amaravati. This series was based on a Telugu short stories collection called ‘ Amaravati Kathalu’ written by Shri Satyam Sankaramanchi.

This is where I heard about Amaravati for the first time. Little did I know then that after almost three decades, I would travel to this town only to come back with a heavy heart.

I was in college in 1995 and had no idea about this little place nestled somewhere in Andhra Pradesh.

Directed by Shri Shyam Benegal, an eminent director of Indian cinema, this small series portrayed heart touching stories. I found the theme song of this series quite melodious and pleasant.

It goes like this- “ There is a town named Amaravati on the banks of River Krishna which is adorned by Lord Amarlingeshwara. The river flows merrily and sings quietly the tales of Amaravati including those of pain and agony. The life here weaves stories of different flavours and the tales of Amaravati spread their fragrance all around.” This song and the voice of the singer are like honey to the ears and anyone who listens to this melody gets curious about Amaravati.

About 35 km from Guntur city in Andhra Pradesh, the town of Amaravati is known for two reasons. A major religious centre due to the presence of the Amarlingeshwara temple, along the banks of River Krishna, it attracts thousands of Hindu devotees every day. The shivlingam is generally smeared with sandalwood paste and decorated with ornaments which includes a crown and the devotees queue up to have a glimpse of the divine.

The second reason is historical as the town once boasted of the most beautiful and elegant Buddhist stupa ever created in the history of India. Commonly referred to as Amaravati Maha-Stupa, this Buddhist site suffered an irreparable loss which still instills great pain amongst Indian historians as well as the conscientious citizens of this country who could comprehend the amount of loss.

Amaravati in Andhra Pradesh has a namesake in Maharashtra. This Amravati, spelled a little differently, is the second largest city of Vidarbha region and ninth largest city of the state of Maharashtra. Vidarbha is a geographical region in Maharashtra which holds two- thirds of the State’s mineral resources. The Amravati of Maharashtra is at a distance of about 153 km from Nagpur, the largest town of Vidarbha.

When the State of Andhra Pradesh was created in 2014, Amaravati was chosen the state capital and the development work began by taking the land from the farmers under an agreement between the farmers and the Government. With the change of the Government in 2019, it was decided that the State would have three capitals. Amaravati was made the legislative capital, Vishakhapatnam, the executive capital and Kurnool, the judicial capital. The matter was challenged in the court and is subjudiced at the moment.

It is known to very few people that Andhra Pradesh was a major Buddhist centre once upon a time. Today it holds to its glory, the remains of some crucial Buddhist monasteries, chaityas, viharas and stupas some of which are exceptionally unique in their architectural semblance.

Amaravati was one such centre, history of which dates back to 2nd century BCE when it was the capital of the Satvahana dynasty. Buddhism gained prominence during this period and Amaravati became a major centre for Buddhist learning and invited people from all over the world.

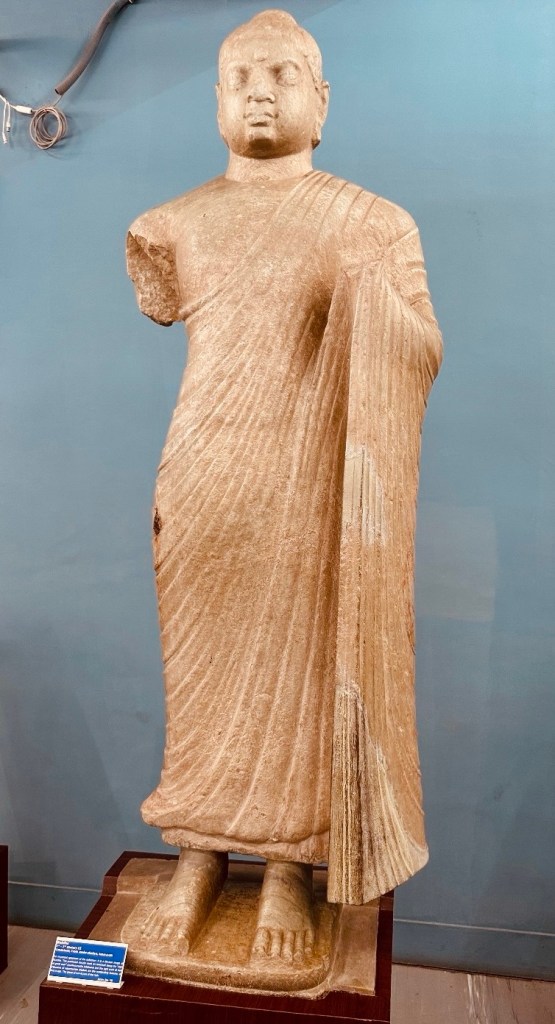

Today, all that Amaravati is left with, is a denuded mound, deprived of its former exquisiteness and grandeur. There is a small ASI museum near the original site which houses some replicas, the plaster caste of the original work and very little remains of actual original artwork.

Everything else has been removed from the site and majority of it is lying in London Museum, another cruelty that India suffered in the hands of colonial powers.

Buddhism grew rapidly during the lifetime of Buddha and even after his death. Buddhist ideas and practices attracted many people in those times who were not convinced with their existing faiths and religions. Buddhism developed out of a process of dialogue with other traditions. India witnessed an era where Buddhist teachings attracted many travellers, researchers, scholars and students from all over the world.

Now, the question comes to mind why Andhra Pradesh and the adjoining areas like Orissa (erstwhile Kalinga) came up with eminent Buddhist stupas especially when this region doesn’t have any such place which is associated with the life of Buddha.

Ashoka, the king of Magadh (one of the Mahajanapadas of those times) is said to be an ardent follower of the Buddhism. In his lifetime, he took a lot of measures to spread Buddhism to every possible corner of the world. It was Ashoka who distributed portions of Buddha’s relics to every important town of this country and other countries too. He also initiated the work of building stupas above the relics. It was during his time, Andhra Pradesh was bestowed with the prominent Buddhist sites.

The relics of Buddha included his bodily remains and the objects used by him. By the 2nd century BCE, a large number of stupas including those of Sarnath, Sanchi and Amaravati were built.

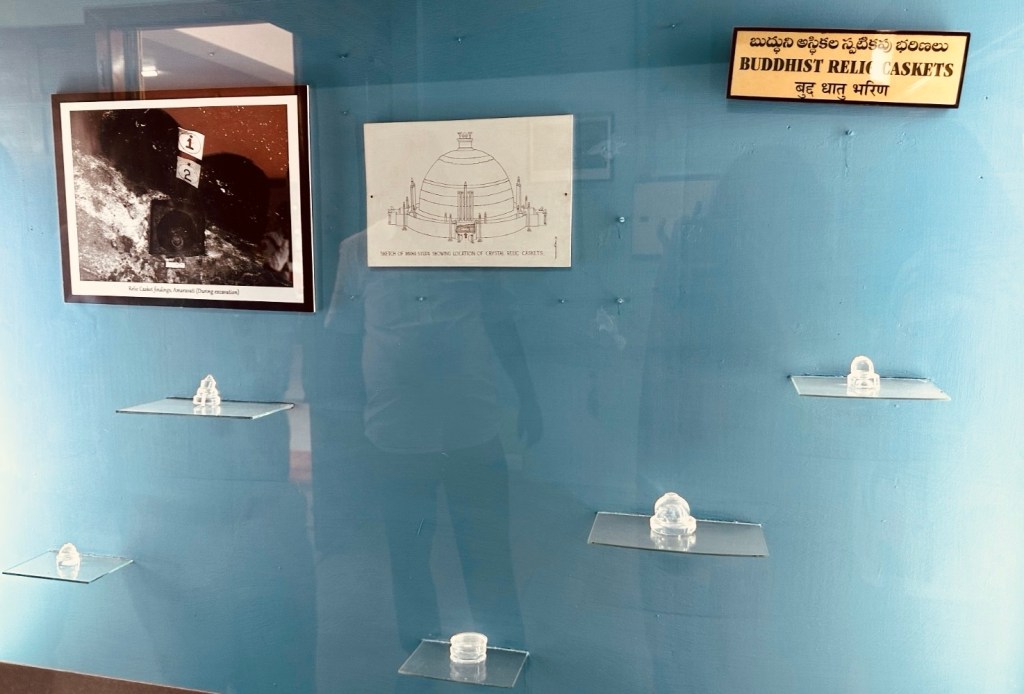

During this trip, we saw the facsimile of one such relic casket kept in Amaravati museum. The ornate caskets were used to keep the smaller crystal cases with Buddha’s relics like one we can see in the picture above. Amaravati stupa had about five such crystal cases, some of which are still with ASI.

The fate of Amaravati can be discerned better when it is compared with the destiny of Sanchi Stupa. It would be appropriate to compare the two sites to fathom better the tragic loss of Amaravati Stupa in the hands of imperial powers and also because of the neglect of the locals.

The class XII NCERT text book in history puts up this comparison in the most perceivable manner. The site of Amaravati was first discovered by a local king in 1796 who accidentally stumbled upon the ruins of the stupa in his quest to build a grand temple in the town. He used the stones from the site to build the temple, however, there is no recorded account. The temple he built perhaps was Amarlingeshwara dedicated to Shiva. The shivlingam in the sanctum is very unique and I haven’t seen a similar lingam in any other temple of this country. To my surprise, it was a thin and tall pillar like structure of about 8 feet or above. It looked like one of the pillars from the gateway of the Amaravati Stupa, one could easily make out from the model of the stupa kept in ASI museum.

Later, a British official named Colin Mackenzie visited the site and found several pieces of sculpture and made drawings of them. These drawings were never published. In 1854, Walter Elliot, the commissioner of Guntur visited Amaravati and collected several sculpture panels and took them away to Madras.

Adding to the grief of the site, many sculptures and art pieces from the Amaravati Stupa were said to have adorned the gardens of the British officials, who cared little about the historical and archaeological significance of these antiquities.

The pieces from Amaravati kept disappearing from the original site, some were sent to museums in Chennai and Kolkata, some were kept in Amaravati museum but majority of panels, pillars, idols and dome slabs travelled to Britain and were housed in the London Museum.

Today, India is left with very little of what used to be the most magnificent and embellished Buddhist site and an archaeological masterpiece. The mishandling of Amaravati marked a dark chapter of India’s history where a monument was stripped of its clothes and was left denuded and barren to bear the agony for years to come.

One of the few men who had a different point of view was a British archaeologist named H. H. Cole. He wrote- “ it seems to me a suicidal and indefensible policy to allow the country to be looted of its original artwork of ancient art.”

He believed that the museums should have the plaster caste facsimiles of sculptures, whereas original should remain where they have been found. Unfortunately, Cole’s advice was not heeded by the authorities for Amaravati. His plea had an impact later and Sanchi stupa was saved from meeting the same fate of Amaravati.

Sanchi survived because with the experience of Amaravati, the scholars understood the value of the ancient heritage of a country and realised how important it was to preserve them where they belonged to, instead of removing them from the original site. When Sanchi was discovered in 1818, three of its four gateways were intact. The fourth was lying on the ground where it had fallen. Sanchi was under the administrative control of the rulers of Bhopal. In fact, first the French sought the permission from the Begum of Bhopal to take away the eastern gateway to France which was the best preserved. The English also wanted to take away some parts of the stupa to their country. But for the foresight, perseverance and determination of the Begum of Bhopal that they were satisfied with the plaster cast of the stupa and the original remained where it is today. Sanchi was fortunate to have a patronage, but Amaravati wasn’t lucky enough.

Amaravati, which once was a thriving Buddhist centre and a paragon of Amaravati School of Art, one of the three major schools of ancient art, is bereft of everything it once spoke of, so gracefully. The Maha-Stupa of Amaravati, which was once the most intricate and magnificent piece of art, is now a chronicle of neglect and ignorance and an insignificant mound of bricks, completely striped of its former resplendence.

Yet Amaravati, the town of stories, weaving for centuries the fabric of human lives, is alive even today. It eternally whispers its saga in the devotional chants of Amarlingeshwara, in the murmur of River Krishna and in the footprints of the ruins of Maha-Stupa.

Leave a comment